WE HAVE THE CATECHISM: WHAT NEXT?

October 24, 2017

From the perspective of church history, the catechism has a past which is fairly well known. The beginnings of the style of book which we call the catechism had its beginning in the 16th century with Martin Luther’s 1529 Small Catechism. Before the Reformation, catechesis consisted in memorization of the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and basic knowledge of the Mysteries/ Sacraments. For Luther, the emphasis fell upon understanding what was learnt, so the Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’ Creed were broken into small sections with questions following each portion. Luther’s Large Catechism emphasised understanding of the articles of the Christian faith and was intended for teachers and others with the capacity to understand. Thus, there were two types of catechism: a simple question and answer book and a book with longer explanations.

From the perspective of church history, the catechism has a past which is fairly well known. The beginnings of the style of book which we call the catechism had its beginning in the 16th century with Martin Luther’s 1529 Small Catechism. Before the Reformation, catechesis consisted in memorization of the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and basic knowledge of the Mysteries/ Sacraments. For Luther, the emphasis fell upon understanding what was learnt, so the Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’ Creed were broken into small sections with questions following each portion. Luther’s Large Catechism emphasised understanding of the articles of the Christian faith and was intended for teachers and others with the capacity to understand. Thus, there were two types of catechism: a simple question and answer book and a book with longer explanations.

The Council of Trent published its Catechism of the Council of Trent, a book of the second type in 1566. It was a reference book for priests and bishops. Other catechisms followed, including some in the form of question and answer. The post Vatican II Roman Catholic Catechism was presented to the Church on the thirtieth anniversary of the opening of the Council on October 11, 1992.

Within the perspective of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Christ Our Pascha - The Catechism of the Ukrainian Catholic Church was published in Ukrainian on June 2, 2011 and was translated into English in 2016. The Head and Father of the UGCC gives a brief history of the emergence of this catechism in a letter of introduction:

The Catechism Christ – Our Pascha continues a tradition of written and published catechisms in the UGCC going back to the sixteenth century. Since then there has not been a century during which a new catechism has not appeared. Among those deserving mention are the seventeenth-century Catechism compiled by the priest-martyr Saint Josaphat, Archbishop of Polotsk; eighteenth-century catechism entitled The Proclamation or Oration to the Catholic World; and The Great Catechism for Parochial Schools published in the nineteenth century. Finally, in the twentieth century, there was the catechism, God’s Teachings.

He continues to indicate the need for this catechism. After the Millennium of the Baptism of Rus-Ukraine in 1988, the emergence of the underground UGCC “... led to the awareness of the need for a new catechism in which the Christian faith would be handed down as part of the stream of our own thousand-year tradition.” For us the question now is what will the Catechism look like in ten years from now? Will it still address the issues of the age or will the text have become obsolete because of further changes in the social context of this world as yet unforeseen by us?

There are many in the Ukrainian Church who are nominal, in that they have not received an adequate education in their faith. They seldom come to Church and when they do at Christmas and Easter for the blessing of their Paschal baskets they have little idea of why they do what they do. The Catechism is intended for people such as these. When they read its text the light of faith may enlighten the path of life for them. This is one step away from the non-believers who may have never entered the Church and who have no idea of God or Christian belief. Dialogue and instruction on the Catechism needs to be provided for these people.

At the conclusion of the 2012 Synod of Bishops on the theme: The New Evangelisation for the Transmission of the Christian Faith Pope Benedict XVI affirmed three principal settings for evangelisation. The first place is the area of ordinary pastoral ministry to inflame the hearts of the faithful who take part in community worship on the Lord’s day. The second area is that of the baptised whose lives do not reflect the demands of Baptism, who lack a meaningful relation to the Church and no longer experience the consolation born of faith. Then lastly, we cannot forget that evangelisation is first and foremost about preaching the Gospel to those who do not know Jesus Christ or who have always rejected him. To clarify the role of Evangelisation further the Ukrainian Catholic Church published its “Program for Evangelization and Missionary Formation” in 2009. In the following extract, it quotes from St John Paul’s encyclical, “Redemptoris Missio.”

Evangelization is part of the very nature of the Church (Vatican II, Apostolate of the Laity #2.). “the whole mystery of the Church is contained in each particular Church, provided it does not isolate itself, but remains in communion with the Universal Church and becomes missionary in its own turn.”

The implication of this is clearly that the Ukrainian Church must be a Church that is fully missionary in its purpose or it is no Church at all.

The Catechism turns to the Catechetical Directory of the Ukrainian Catholic Church (1999) for guidance in how best to approach catechesis when it says:

Life is a pilgrimage in which we cooperate with God in order to arrive at the future kingdom. ... With our limited abilities, we can never know or love God enough. ... Every adult must come to an awareness that, in order to attain salvation, it is necessary to continue one’s education and growth in the faith (p.61).

The journey of life and the journey of faith merge. This is a journey of growth into eternal life where human desire merges into limitless knowing and loving of God. Furthermore, the directory stipulates a general principle for the shape of a program of development and formation in the spirit of Eastern Christianity:

The program of development and formation in the spirit of Eastern Christianity fosters the creation of a special Eastern-Christian witness in a manner, peculiar to the Kyivan Church, and yet meaningful to the contemporary person (p.70).

This is an important principle which establishes that the Ukrainian Catholic Church which has a specific identity, but which must constantly reform its life in conformity with the Gospel. A catechism suitable for the needs of the Ukrainian Church must reflect the particular form of the mother Church of Kyiv, but it must also do so in a language capable of being grasped by contemporary people. This challenge means that in one sense the work of the catechism is never fully completed. As life forms develop and change the catechism must continue to address and communicate meaningfully with the world.

What are the new directions which flow from this catechism and therefore indicate the future development at least of the catechesis of the UGCC? This catechism does not take the form of questions and answers it is rather more like the longer catechisms of the past with longer explanations. It is also a catechism which speaks the language of Eastern Christian Theology. It is unique in the sense that many times it takes a position which is a compromise between various theological factions in the Ukrainian Church.

It must be admitted that dramatic cultural changes have taken place in the modern world which have had profound effects on the religious life of even devout Catholics, at least in what we call the West. Even Ukrainians have been susceptible to these changes which often go under labels like modernity or even postmodernity. As people across Europe moved from life in the village into the mass urban structures of the city a profound transformation took place. Thus, the process usually called secularization is above all a process of reconstructing belief and even religious practices. Scholars refer to the disenchantment of society. Here we have a paradox. On the one hand, there is abundant evidence to support the view that modern societies are destructive of conventional forms of religion. On the other hand, modern societies cannot live without some form of religiosity.

Corresponding with massive social change, many Catholic Church communities including the Ukrainian Catholic Church in the diaspora have experienced the loss of their youth at least insofar as regular Church attendance is concerned. The phenomenon of adolescence and youth as distinct stages in the life journey are products of the twentieth century and beyond. The prior arrangement allowed little space between childhood and the commencement of work at least for peasantry throughout the feudal period and into the industrial revolution. The following citation highlights the changes which brought about the stage now known as emerging adulthood:

The steps to and through schooling, the first real job, marriage, and parenthood are simply less well organized and coherent today than they were in generations past. At the same time, these years are marked by extended freedom to roam, experiment, learn, move on and try again.

So the factors which have influenced and shaped the lives the young in society are clearly delineated especially by increased availability of higher education for most if not all; the delay of marriage until the end of the third decade of life and its implications for the sexual activity of the mature but unmarried; economic changes including the undermining of career stability in the work force; continued parental financial support of their adult children. The result of these social trends is that Catechetical formation will need to change drastically, if it is to be effective. Rather than learning formulas from a book Catechesis might be more like a series of steps in a process of formation. In some ways this is not completely new in the life of the Church. If we look back in history to St John Climacus we find that he offers a formula in multiple sages for the growth of the spiritual life. The spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola were meant to effect conversion and ultimately commitment to Jesus Christ by undergoing a process during 40 days or recent times eight or even two days in a shortened form. Eventually he also adapted the Exercises for people could only visit a retreat director four perhaps an hour each week. This adaptation, called the 19th Annotation, forms the basis of much formation work and is the background to much of the written work of Fr John Paul Gallagher, SJ.

In 1987 Jesuit priest, John Paul Gallagher wrote a book entitled Free to Believe: Ten Steps to Faith. I think it is helpful today because it is a book about faith, but also about “bothering to be free.”

The first section of Gallagher’s book describes getting free as a series of four escapes; firstly. from a false self, imprisoned in negative attitudes to a true self; secondly, from the pressures of a superficial context to the courage to live more contemplatively and find an alternative community for support; thirdly from thinking about God in ‘out there’ language to the wonder that can reverence Mystery; and fourthly, from the immature gods of childhood images to the human face of God revealed in Jesus Christ. He offers as food for thought the following passage penned by the Irish Catholic Bishops to mark the International Year of Youth in 1985:

Some people carry around with them an image of God that is in fact superstitious. It is the image of the punishing puppet-master who has to be humoured and pacified in case he might pull the wrong string. Others picture him as a distant, inaccessible authority figure who is totally out of tune with the friendship held out to us in Christ. A surprising number of people look on God as a kind of clock-maker — a God of explanation for the universe but a God irrelevant to ordinary life. Here are even those who only know him as a God of the gaps. He has no compelling existence until favours are needed or trouble strikes. . .

The only God worth believing in is the God who believed enough in people to die for us. The only God worth living for is the One who calls us to live with him, through dark faith in this life, and beyond death in face to face fullness. The only God worth searching for is the One who searched for us and who still struggles within us in order that we may become more free to love.

Thus far our author has sifted our true from false approaches to questions of faith and to discern true from false images of God. From this point forward we begin the search for God in four steps. This amounts to a powerful argument toward the possibility of faith. I am relying heavily on Gallagher’s book, Free to Believe (1987) from which I will quote freely. The first step is that of the heart that follows its hungers, staying with its restlessness, waiting until the time is ripe to say ‘yes’. This is the road described by St Augustine in his Confessions where he says, ‘you have made us for yourself and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.’ Is life itself unsatisfying and not the whole story? This is typical of the search for meaning as experienced by many of todays’ youth.

The second step is that by the mind that seeks for meaning wrestling with the many ‘why?s’ of existence. For most people knowledge about God would start from revelation, simply because they did not have the opportunities to ponder everything in depth. The road to God actually starts from something very simple – a sense that this world in itself does not explain itself. Is there a pattern behind existence itself? Why are we here? Why does the world exist at all? Must it have some origin and some purpose? Trying to answer these questions can lead into labyrinths of complexity. But if they are raised in the right spirit, then even pondering the questions can prove a pointer to God. These are questions well known to those who work with adolescents. The questions have an urgency which demand exploration rather than quick and ready-made answers.

The third step is that by the conscience, awake to self-deceptions and to the scandals of our divided world, yet struggling to discover what is right and best. Start with self-reflection on the experience of conscience. Continue to ponder with reverence the probability of God. Such roads may lead to a ‘real assent’, a personal surrender well beyond the bounds of a merely intellectual truth. Short lived generosity is easy. How is the whole of life to be lived in ways that matter for others? That is the more frightening question – tougher, long term, costly to self. To face that question is to encounter a twofold struggle of good and evil: within the value systems of the world and within the battle zone of each self. To stay faithful to that experience of struggle is hard. It means encountering demons in various forms. There is the demon of despair born from the sheer enormity of the world’s pain. There is the demon of guilt born from the constant failure of the self to live one’s own hopes. The object here is to elicit a sense of life as call. This is most consistent with the spiritual journey refered to earlier.

The fourth step is that of the inner spirit that does not run from silence that experiences something of its own depths, and learns there to listen for God’s word. People claim that they have had experiences that come from God: they offer no proof except their own overwhelming sense of his presence. Since it often forms the bedrock of people’s quiet confidence that God exists and that they have known him, it must at least be listed as one of the great pointers towards faith in God. If there is a God, he must be encountered most in the ordinary. This kind of step is more typical of those coming into what is called young adulthood; somewhere around the late twenties or early thirties. It must be said that some come a greater and more intense spiritual awareness than others. Spiritual guidance of the sort just described will often enhance the thinking and reflection presumed by this last stage.

In conclusion, I offer some pointers for catechists and others who engage in the catechesis of youth. The formation of catechists is fundamental to both the teaching of the catechism and the work of evangelism. Catechism classes must continue to be held, but evangelisation by younger committed youth workers is an essential element in the future life of the Church. Not everything we have done until now is without merit – but we will have to listen to the signs of the times and respond to the needs of todays’ audience. Our youth has not rejected – they are not committed enough to practice what many know they should. We need a focus on all our situations which have the objective of speaking or associating with the people in front of us. The catechism is not just a textbook meant for the classroom, but it is intended for the broad community of faith as well which needs constant catechetical enrichment. We are a family of faith in which Christian catechesis is communal as God is a relationship. This relationship is experienced when we participate in parish liturgies, in school activities. “Faith is caught not taught”. That frequently heard mantra is meant to remind us that there is more to faith development than just instruction. In time some things will need to be learnt also but initially faith is something that wraps itself around one. Christian actions or deeds result in a shared faith.

The following interactions are some of the essentials in faith development:

1. Prayer - constitutes the relationship of the believer with God and contains the following elements:

• Personal prayer in which one uses one’s own words to express one’s love for God

• Set formula prayers such as the Lord’s Prayer which help form one’s heart according to the mind of the Church

• Communal prayers such as the Divine Liturgy, the Hours, Akathists and Molebans extend these formulaic prayers

• Meditation in which one places oneself in the presence of God and follows a formula such as Lectio divina which includes the following steps: Lectio (reading) to understand the text; meditatio (meditation) to discover what the text says to me; oratio (prayer) in which I respond to the text; and contemplation (contemplation) in which I ponder what is asked of me.

• Silence in which one is still and quiet in the presence of God

• Icons which have such a profound effect in all Christian prayer because they are the windows through which the believer is able to see the heavenly kingdom.

2. Parish

• As a place in which to meet God in prayer and fellowship. The Church’s liturgy encompasses many of the elements of the practices of prayer just described. More importantly the assembly of people that constitute the Church are in fact the Body of Christ that builds the kingdom of God here on earth

3. Fellowship

• Speaking and sharing with people who have a Christian vision is a very important way of bringing about the fulfilment of the Kingdom of God

• The assembly of people which constitutes the kingdom of God (Church) includes friends, older people and clergy

• Learning by sharing and listening are the ways by which the Christian believer grows in faith, hope and love.

Catechists must be chosen from amongst the believers and those who practice their faith because no one passes on what he or she does not already possess at least to some degree. So, while we will need to teach catechism we also have to approach certain people as if they are not familiar with God at all. We have to introduce the concept of the possibility of a divinity that has a plan for us. This is the challenge – we want the steady as it goes approach – we have to focus on the new vision for the Church. Rome, our Church, has actually been talking thus for many years now. The Church is well aware of the problem we are talking about; its just that we have not noticed it before. We need to pay attention to the signs of the times. This requires a blessing, grace – a gift from God.

Without a framework of spiritual searching and questing such as that suggested by Gallagher there will not be much point to the Catechism. It is a book that can serve the future well but only if it is received and used reflectively.

Clearly we cannot continue in the way we were. We should we go forth renewed in prayer and personal holiness

This is a spiritual struggle according to St Paul, for our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. (Eph 6:12) that is why those who will lead the Church should be totally dedicated servants of God. We need to start work and finish our work totally dependent on God.

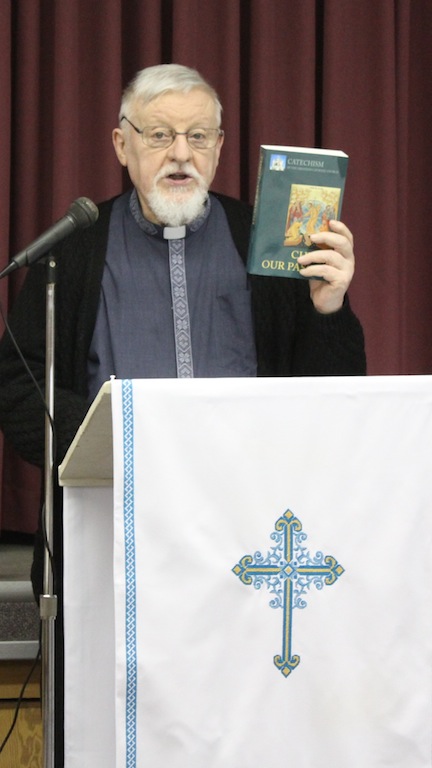

The Most Rev. Peter Stasiuk, C.Ss.R.